What Does “Value of Solar” Mean? And Why Does Everyone Fight About It?

I’ve heard feedback from you.

Some of you tell me that you have benefited from my campaign blogs and videos that attempt to translate complicated voting rules or energy concepts in to more manageable, albeit wonky, nuggets of policy goodness.

Thank you for that. If there were ever an election that could benefit from translation, this is it.

So, I want to briefly explain a concept to you that utilities, and SRP in particular, have been debating for years: “value of solar”.

When energy policy nerds debate the value of solar, they are talking about whether “distributed solar” has a net positive or a net negative impact on the over-all health of the energy grid. Distributed solar can mean residential solar, or business solar —like solar on parking structures or warehouses.

Why does this matter?

Because some would argue that customers without solar panels are paying more for their power because customers with solar panels are paying for less of the maintenance and operating costs of the total grid.

Wait. Don’t leave.

I know the temptation is strong right now to slide over to YouTube and watch videos about dog training or English tart baking. But I promise to get the most important points out quickly. Then I can bullet point what I believe SRP should be emphasizing to make this entire debate almost mute.

Here are the top four debate points that you should understand, and come in to play as SRP continues to raise rates on residential customers the most.

I’ve borrowed heavily from two studies. I’m not saying I agree with them completely. But their is a lot more out there, such as this Berkeley study. There are almost as many value of solar studies as there are states. So, for the benefit of explaining these ideas, I tried to keep it simple.

1. Cost Shifting

Utilities have argued that solar customers force non-solar customers to pay for more of the maintenance and operating costs of the utility. SRP board members have said this a bunch over the years.

It turns out that, while this can be true, depending on the state and utility. The reality is that in Arizona, any cost shift is most likely to be less than $1 per month. This has been reported in a Trump administration study from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL).

Solar proponents argue that such a small cost shift, even if it occurs, is more than worth the clean air and water conservation benefits of not adding more dirty, water-wasting fossil fuel power to the system.

Many residential and business solar owners in SRP territory report that they are paying anywhere from $20 to $50 per month just to have solar —virtually erasing the savings that solar could otherwise provide. SRP worked under a rate structure for the last decade in which solar owners were charged a much higher “grid access charge” every month than non-solar owners. Think of it as a higher monthly membership fee.

Last year SRP made the monthly grid access charges the same for all customers, but is now charging solar owners much more for the electricity that they buy from SRP.

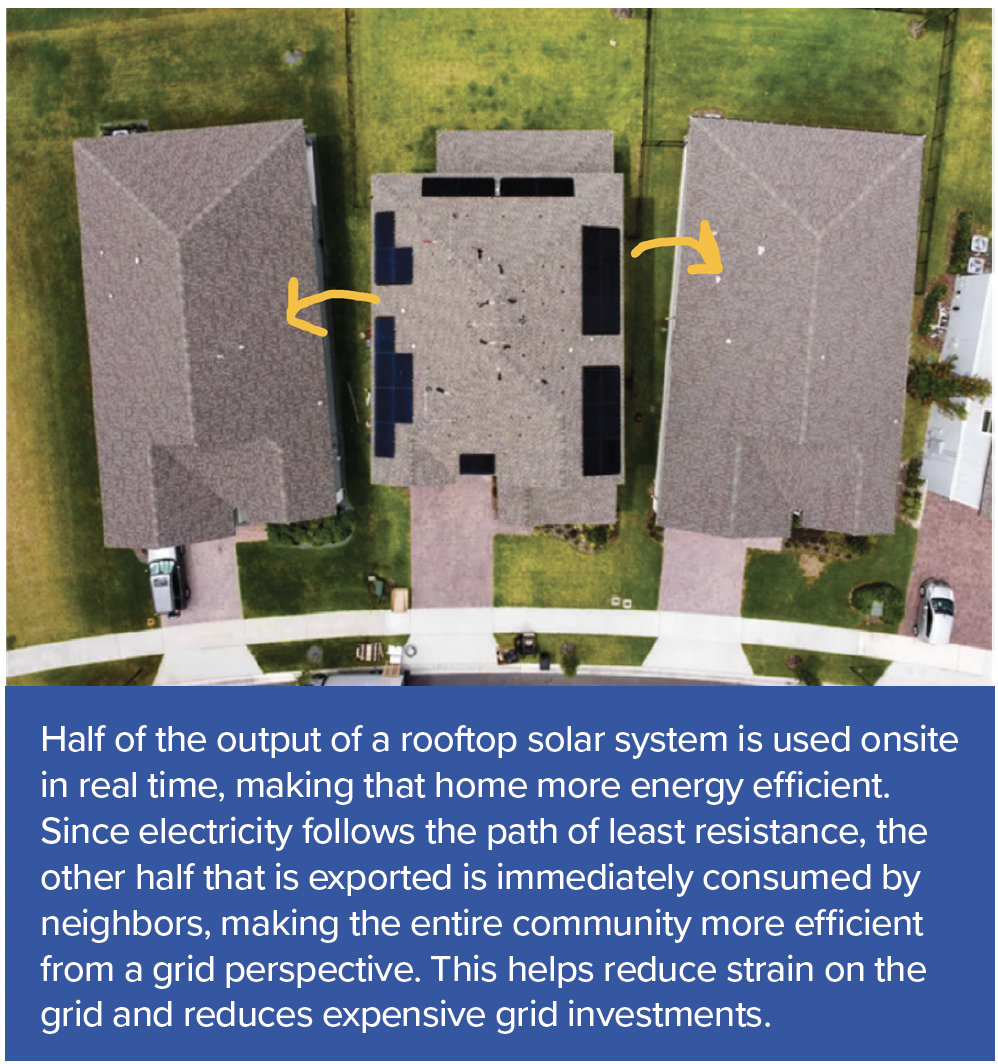

Advocates also dismiss the cost shift argument, saying that the utility benefits from the way that solar on one house feeds its immediate neighbors, thus stabilizing the neighborhood grid.

2. Reducing Expected Growth

The idea that a cost shift is happening from solar to non-solar owners is otherwise referred to as “departing load.”

It’s a fancy way of saying that the utility has fixed costs that somebody has to pay. If solar customers are using less energy, then they are necessarily paying less in fixed costs.

There are two problems with this, in the minds of solar supporters. First, most fixed costs are represented on a customer’s bill as fees on top of what you are paying for electricity. Those don’t change that much if you have solar. Second, maintenance and operating costs for the utility are small by comparison to the huge cost of adding new power plants.

And, since solar owners (especially those with batteries) are reducing over-all system demand significantly, there is a savings for all customers over what we would all pay if we had to add more generation capacity.

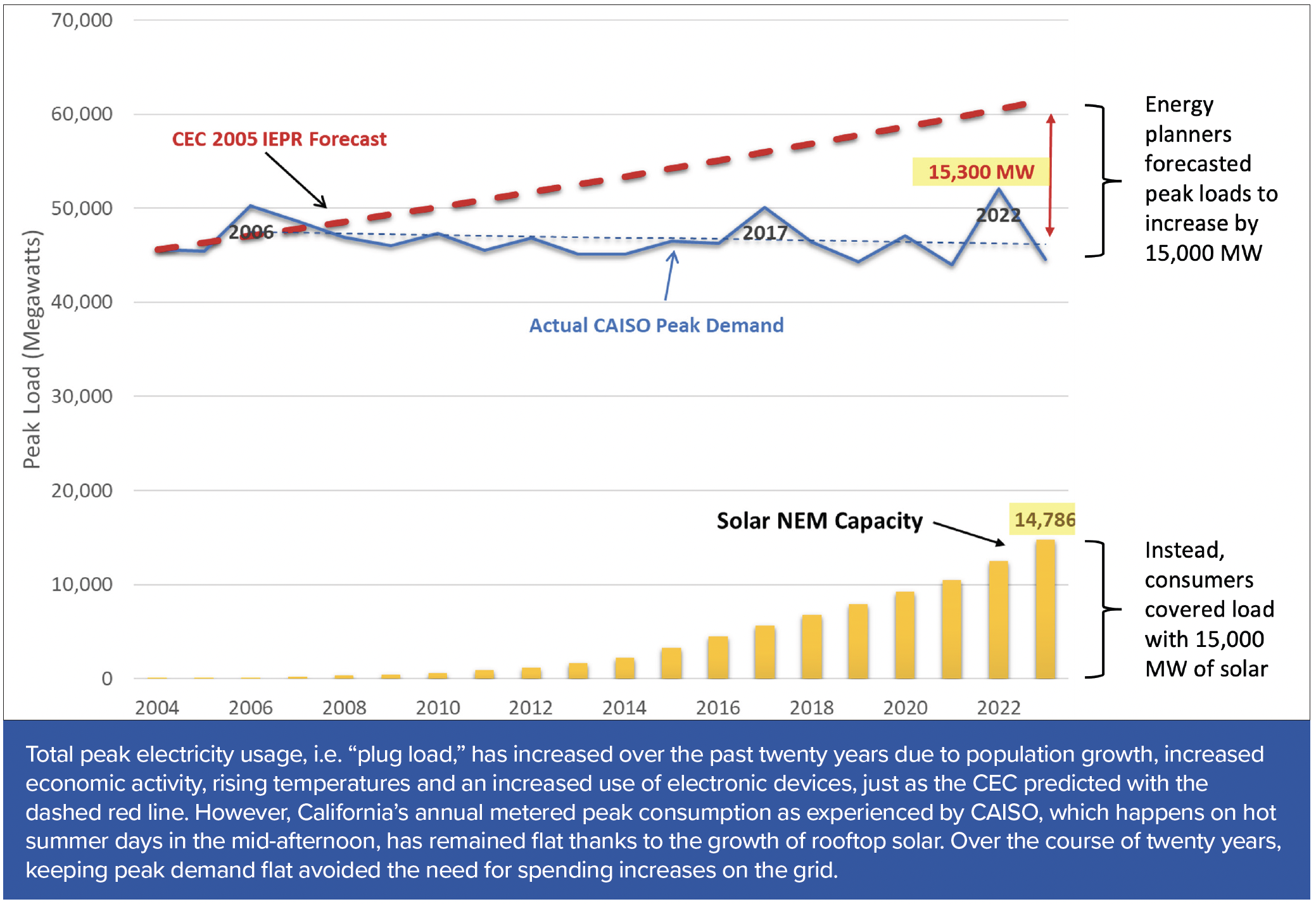

Because I could not find a similar study for Arizona, I’m borrowing from the California study again as an illustration of this concept.

If anybody out there knows of an independent Arizona study, I’d love to see it.

3. The Duck Curve

The “duck curve” refers to how there is a huge increase in demand as the sun goes down, especially in areas where solar panels have been delivering power during the middle of the day. It is a justification for adding a bunch of new gas capacity that can turn on at dusk.

I did a video about this during my road trip in 2024, where I explained it all on a “white board” on the side of my blue van.

I think folks have taken a truly reasonable concern about the duck curve and they’ve weaponized it against innovation.

There is a solution to this: increase energy efficiency measures, home batteries and EV charging, which can “shift” the power available from the middle of the day to after the sun goes down. More on that below.

The argument is made in the California study, above, that the more important conversation about peak demand is not the one that happens each day, but how solar has avoided more extreme peak demand in the highest demand months of the year. This has avoided the cost of many new power plants.

I know. I know. Some of you reflexively hate on California. Their customer bills are higher for many reasons. But to say that it is due to renewable energy is to severely misunderstand a complex energy system there. You can hate on California and also benefit from lessons learned.

4. Solar is only for the rich?

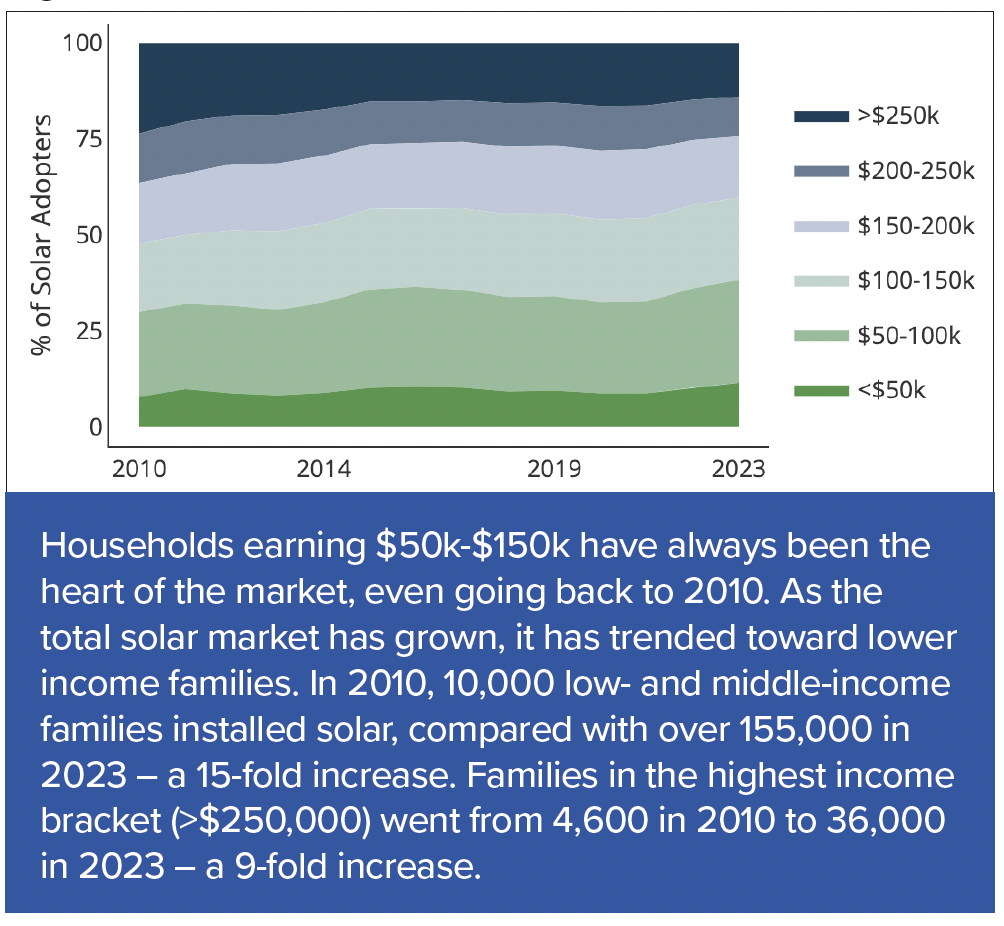

Folks make the argument that wealthier customers who install solar are shifting costs to the poor. This is a variation of the cost shift argument.

But it assumes that the cost shift argument is correct.

Again, because I’ve not seen Arizona studies that break down solar ownership by wealth, I’m sharing the California study.

I’ll repeat. If anybody here knows of an Arizona study like this, I’d love to see it.

Regardless, we should be helping lower income folks and small businesses gain access to anything that saves energy (insulation, solar, batteries, appliances) because the more we save in aggregate, the less we all pay to install expensive new energy.

The take-away

Thank you to those who have made it this far. You can return to your more entertaining distractions shortly.

If elected to the SRP board, I want to focus more on a whole list of options that shift the duck curve and avoid expected demand growth. I don’t think it’s realistic to shut down every gas power plant tomorrow, however.

My policy focus will include “virtual power plants”, increased energy efficiency measures, requiring data centers to source their own clean energy and incentivize car charging in the middle of the day, rather at dusk.

I’m going to explain virtual power plants (VPPs) more in future blogs.

In light of new trends in lower battery prices, such as sodium-ion, redox flow and many others, SRP needs to revisit its older solar projects and add additional battery capacity. This is much cheaper than paying for water-wasting, dirty peaker plants that sit idle for most of the year.

SRP needs to build price signals in to the requests for proposals (RFPS) that power plant developers bid on. Those signals need to reward long-duration battery storage that can dispatch quickly and is designed to stabilize the grid.

We need board members who are willing to think creatively.

I will be that board member.